After the A is for Awesome and B for Beautiful (Boat + Pearls) posts, consider this a palette cleanser. Something pleasantly astringent and provocative, I hope, so we can taste what’s coming next with more nuance. Because when you do a trip like this, it is striking how fast the ‘awesome’ becomes normalized.

More broadly speaking, it’s intriguing how quickly we humans get habituated to certain experiences over time from the good, bad, ugly, dull or extreme. Our exceptional situation notwithstanding then, there is a pattern here that extends to all, making this worth a short segue.

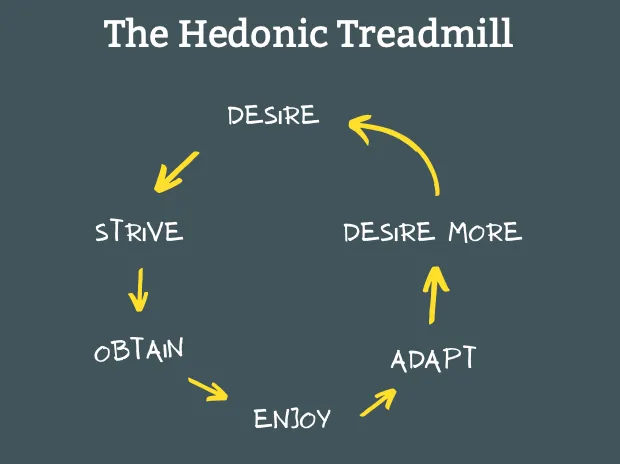

Cognitive psychologists have dubbed this the “hedonic treadmill.” A fascinating evolutionary feature, this emerged as a way to ensure human survival and reproduction, especially when the striving got tough. Indeed, for most human history (like 99.99%) getting around these hedonic bases wasn’t easy; being successful at the “obtain” let alone “enjoy” step was a rarity.

Once humans got more settled (around 10,000-15,000 years ago) new constraints co-evolved with our brain chemistry: different religions, cultures and economic systems interceded, shaping and dedicating what was deemed desirable, how much desire was acceptable, and who could do the desiring, and so on. (If you had the good fortune to grow up with immigrant friends like I did, you saw how concepts of happiness differed across cultures. Tiger moms, bless them, are a cliché for a reason.)

Flash forward to our present day. Terminal scarcity has given way to abundance for many. Billions have been lifted out of poverty—perhaps the most under-appreciated miracle of our time— in a large part because we have global market economy that has made a virtue out of exploiting our human desires, needs and wants

Given our finite world, this couldn’t last indefinitely. Like a snake eating its tail, without constraints this positive drive mutates into a vicious cycle that is hard to break. Tracking our brain chemistry and dopamine in particular, the treadmill explains concisely—and I think usefully with a less judgy sting— everything from shallow consumerism where we keep buying things yet feel less and less satisfied to many social addictions from the opioid and obesity epidemics (most notably in the US) to the steep rise of teenage anxiety and suicides driven by the compulsion for devices and social media.

This treadmill also explains the Silicon Valley ‘grind culture’ and across all high-status positions, toxic careerism, where people stay far too long in positions that no longer serve them or anyone else around them.

All of sudden, this wonky thing we never had to think about needs rethinking if we want better futures for us and the planet. Now an entrenched social algorithm running throughout our economy and society, the question is how do we hack this evolutionary feature to be beneficial, rather than maladaptive, across scales from the individual to global level?

The Practice of De-habituation

I bring this bigger picture to mind, not to bore you I hope, but because it provides one of the rationals for why we disrupted our work lives to do this circumnavigation. It also provides a framework to talk about how I (we) are adapting to the new treadmills we find ourselves running on.

Feeling like one big roller coaster ride, this might explain why it’s impossible to pin-point our emotional location at any given time, our track resembling more of figure-of-eight spin around happy, sad, confused, conflicted, exhilarated, exhausted, joyful, feeling silly, content, relaxed, frustrated, stressed, annoyed, uncomfortable, bored, and back on around again.

But let’s return to the questions I started with at the top: how do we deal with the new getting old very fast? How do we live with the initial euphoria of an adventure retreat into the hum-drum? And perhaps unique to our situation, how do we deal these complex and conflicting thoughts when undertaking such a privileged trip?

The practice I am leaning into, specifically, is called de-habituation. Just as it sounds, this involves intentionally disrupting your habitual ways of experiencing an activity or event. Like a good scientist or artist, the idea is to pause and see something new, whether it’s an every day routine, unusual encounter or peak event. The process is the same either way. And like meditative practices, simply being more aware of where you are in this cycle can be the difference that makes the difference.

Speaking of which, the damn Buddhists were about 2,500 years ahead of us in anticipating the dark side of the hedonic cycle and have been offering spiritual solutions ever since. Ditto for Aristotle who also wisely taught that wellbeing followed the pursuit of “the good life” (i.e. doing ‘good’ and in moderation, alas not the party-hardy kind.)

With these old guys not being everyone’s predilection, thankfully scientists have been picking up the monk’s scent, studying the multi-faceted nature of happiness and well-being, not coincidentally for a global market of people feeling increasingly less happy and less well.

So how is going so far on Skana? For us, de-habituation is both easier and harder. It is easier in that as we sail around the world we are constantly interacting with exotic new places and contrasting contexts. Novelty seems to be signature cocktail served up several times a day, whether asked for or not; and our worldly assumptions get both shaken and stirred, when we least expect it.

Photo: Port Resolution, the island of Tanna, Vanuatu (July 31, 2024)

Take this rather over-the-top yet irresistible example. We recently anchored in Port Resolution on the remote island of Tanna in Vanuatu, the last country in our grand cruise across the South Pacific. As we were settling our anchor, grateful for a safe passage from Fiji and taking in the rugged lush beauty around us, we noticed something peculiar.

Shooting up from spots amongst the craggy basaltic rocks just shy of the shoreline, we saw white puffy banners being expelled into the air. What were they? Mist from the surf? No. Can’t be that. We could see more cotton candy plumes higher up as well, dotting the jungled hardwoods. Snippets of marine layer cloud? No, not that either. Their shape and texture wasn’t quite right and there was a strange pattern to their periodic bursts, not random but not predictable either.

And then it dawned on us in an instant. They were fumaroles or volcanic steam vents. Connected to a thermal network deep below, these surface holes were releasing streams of blistering hot water vapor, the exhalations of a mother source still unseen, somewhere over the next hill. Borderline giddy at this thought and enchanted by the Circe du Soleil artistry of this display, my fired-up imagination half expected Puff the Magic Dragon to poke its’ head through the trees at any moment.

Then at night, looking up over our dinner, their mother source was revealed, the unmistakable crimson glow of the volcano’s caldera emanating behind the ridge—a mind-blowing reminder of our connection to the fiery life-source of our planet.

If my colorful description of this scene isn’t proof enough, this rotating roster of novelty is a delightful gift that keeps on giving. The mixed blessing, however, comes in finding the right pace, wherewithal, and time to drink all this all in a way that does these experiences justice. Most of the time I feel we aren’t.

I know this is just another expectation we’d be wise to drop. Channeling a cognitive psychologist, constant “context-switching,” they would say, is one of the fastest ways to drain our energy-hungry brains and this in turn impedes our ability to fully integrate and make sense of what we are experiencing. What’s needed is some kind of mental swale to let all of this infiltrate and sink in. And that is of course why I am writing as much as I am.

So, to recap: just last week it was volcanos and running around with the Lakel tribal people on Tanna (photo below). Totally surreal— and a topic for another blog.

This week it is the opposite. We are cooling our jets in a western-ish marina, situated in a far-flung postcolonial outpost in Vanuatu, a place still clearly recovering from a tricky tangle of colonialism, corruption and cyclone disasters, with us eating too many burgers and fried calamari while wondering how to make the best of our time stuck in a place we didn’t want to be because of some pretty major mast repairs.

Photo: Jackie with kids of Yakel village tribe, Tanna, Vanuatu. August 2, 2024

Deadening effect of wealth (and experiences?)

Having said all of this, this adventure makes it harder to de-habituate as well. The hedonic cycle explains this too. Like drinking alcohol, these experiential hangovers are boosting our tolerance levels.

So accustomed to extraordinary experiences, my 12 year old shrugs off a mere snorkel if the corals aren’t 100% healthy (many of them are not, I am sad to report) or eschews a walk in a picturesque village with local kids “because she has been-there-done-that.”

Photo: Bored 12 year old. Protruding feet belong to helpful-Hugh from Ri Ra trying to lift her spirits.

Such habitation is both disheartening and concerning. Especially given my opening piece about how easily the hedonic treadmill can run amok for people and society. And especially if one follow’s the journalist George Monbiot’s logic (see quote below).

"Some [extremely wealthy] are lively, curious and engaged, but among others I’ve repeatedly noticed the same thing: a dullness of spirit. There’s a sense that nothing is sufficiently stimulating to hold their attention, that they have lost their capacity for wonder." - Journalist George Monbiot, Extreme Wealth Has A Deadening Effect on The Super Rich

Of course, given that a lot of this brain chemistry hi-jacked by consumerism, one doesn’t have to be super rich to be vulnerable to this tendency, particularly with devices and social media distorting our perceptions of reality, one dopamine hit at a time.

I have noticed another thing. We are constantly taking stock and comparing. This seems innocuous enough. But this mindset can ratchet up the hedonic bar higher and higher if you are not careful. For instance, a dinner topic might revolve around a “which was better” conversation: the “Wall of Sharks” dive in South Fakarava (Tuomotus, French Polynesia) or diving with the Bull Sharks in Fiji? A ridiculous dialogue, of course, on so many levels. Yet we can’t seem to help ourselves doing this ranking and spanking, categorizing and evaluating.

Photo: The “Bull Shark” dive in the Yasawas Islands, Fiji. July 2024. Jackie and I were diving with them, just meters below this photo. When I shared this with the OWR women’s thread (aka the Pearls), I felt the need to add the #badmother hashtag

Friends and family ask well-meaning but impossible questions too like: “what’s the most interesting place you have visited so far? I usually divert the conversation then, our brains too full to answer, and with the growing realization that this kind of comparative thinking has a narrowing effect while putting us right back on that hedonic treadmill. As my favorite dark Dane, Søren Kierkegaard (1815-1855) put it best, “comparison is the great modern evil.” But how do we stop?

A partial answer is to resist early evaluation and any firm expectations of what this experience will feel like. Though if we can’t help ourselves, to judge them lightly, resisting those insidious voices of cynicism or critique or show-off cleverness, which can be reductive and suck the vitality out of these moments and memories in short order.

Another strategy is keeping the individual integrity of these experiences in tact as much as possible, cherishing them accurately and generously for what they are, while noticing their inter-connectedness and patterns. For already, much is starting to blur and swirl into a (mostly) delightful, dynamic mosaic!

Photo: Garden of the Sleeping Giant, Viti Levu, Fiji, (July 2024) . This place was owned by the actor Raymond Burr of Perry Mason fame as the home of his orchid collection. I love the quirky resourcefulness, making this out of old umbrellas and other found objects, all of which made me “look” more closely.

All of this means, when we get another staggeringly beautiful sunset, or discover dolphins playing in the bow of our boat, the practice is to notice something new every time and not take it for granted. These are privileged challenges, for sure. Yet I can already see how this can apply to normal activities as well, re-perceiving sights and sounds and smells in different ways when we return home. The journey of discovery doesn’t have to stop.

Acts of appreciation and gratitude work incredibly well too. Put aside the loaded words if you find them too New Agey, this is a timeless technique. This is what all the best mothers, fathers, teachers and mentors have tried to teach us. This is what all the best spiritual traditions reify as well. Finally, this is what scientific data is backing up too in countless studies. For me, half-skeptic/half-seeker, I don’t think I could do this adventure as adequately or sanely without them.

Whatever your method, above all, starting from a place of wonderment makes everything just that much easier.

With this mouthful to chew on, stay tuned for the next course: “C is for crazy” and “D is difference or deviant” where we will resume the heady race through my A,B,C,D,E acts of wonderment.

Resources

- For de-habituation, see “How to Make Things Sparkle Again.”

- The book Look Again: The Power of Noticing What Was Always There by Tali Sharon and Cass Sunstein (2024)

- For the negative effects of social media and devices, see the influential piece, “The Terrible Cost of Phone-based Childhood” by Dr. Jonathan Haidt.

- Also see Dopamine Nation: Finding Balance in An Age of Indulgence by Stanford University’s Dr. Anna Lembke.

- Why do I know this wonky stuff? As a foresight/futures specialist in the think-tank world, I most recently worked on rethinking sustainable lifestyles and reinventing extractive business models to be more regenerative . Apologies for all the disparate links. I just discovered that my home website is not working and I don’t know why. (Ugh!)